Souleyman has crossed over and his music is swimming in new expectations and understandings, his image negotiated by rock reviewers and journalists. She complained via a phone interview that Sublime Frequencies would take a scratchy Souleyman track and make it “ten times scratchier.” She said to expect a more “contemporary” sound in the future. There has been no official announcement of a new record, but this would be Souleyman’s first album recorded in a US studio - a big divergence from his previous four albums, all compilations of Syrian or Western live shows, released through his former label, the Seattle-based Sublime Frequencies.Ībout two years ago, Souleyman broke from Sublime Frequencies and took on a new manager, Mina Tosti. On the eve of Souleyman’s latest European tour in April, British electronic musician Four Tet tweeted that he had “just finished mixing this Omar Souleyman record.” The biggest change, though, is still forthcoming. Broadcast on the satellite music channel Al-Ghinwa, scrolling text at the bottom of the screen sends well wishes to the Saudi King on National Day. In a more surreal turn, one of his latest locally produced music videos is a mash-up of clips from his Western shows with an Arab lounge-style performance. Björk’s NPR nod turned into three Souleyman remixes on her 2011 Biophilia album, and the most common YouTube videos of the Syrian performer are now shot from side-stage at global musical festivals or even his own US–European tours. Years later, like the Syria alluded to in “Leh Jani,” Souleyman has changed. Context and the dissemination of Western cultural detritus in Syria are something you have to be there to better understand. Omar and his group have never heard of Elvis or the Beatles, yet they know Michael Jackson, George Michael and Celine Dion. It was an environment that Gergis hinted at in a 2010 interview: Glimpses of pop culture are buried in the frenetic pace of the video and song.

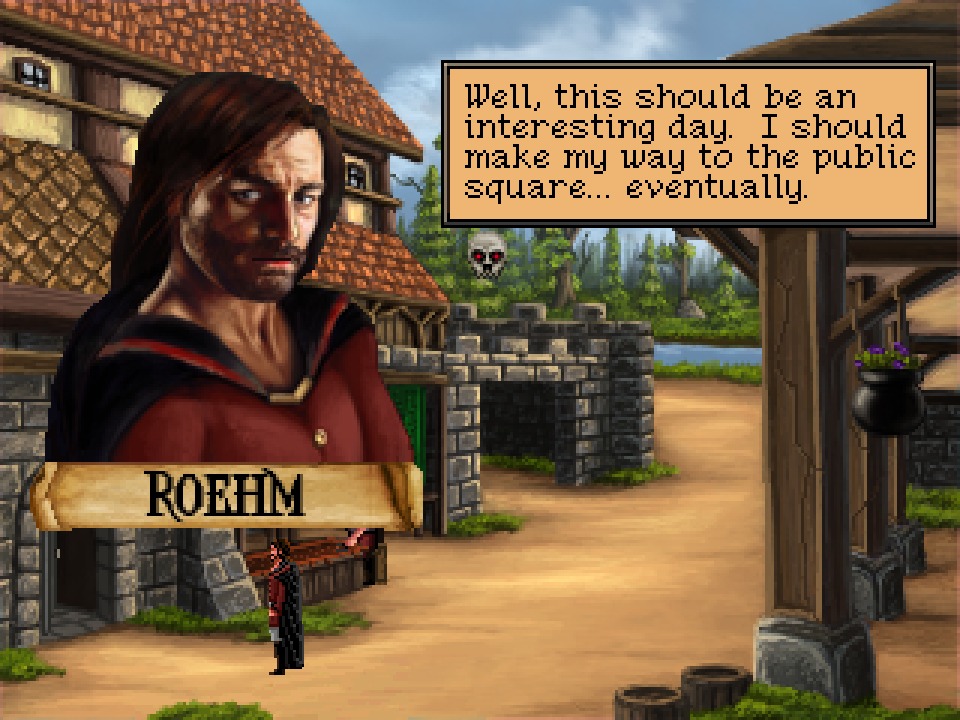

#Quest for infamy kurdt windows

For each “Leh Jani” scene that shows dollar bills raining on long-haired women in glittery gowns, there are companion scenarios in everyday Syrian life, like the street vendors who sell posters of Bashar al-Assad, face framed in a heart, alongside Titanic-era Leonardo DiCaprio neon palm trees that glow outside a Hollywood-themed restaurant named Street of Stars a minibus that has a dashboard covered with red velvet hearts, its windows plastered with Nizar Qabbani couplets. The video hints at a kind of cast-off culture, street kitsch, that is pervasive in cities like Damascus. Gergis was able to capture in a single video some of the bits of Syrian pop culture ephemerata that surround dabke musicians like Souleyman - things like the on-screen streaming of text messages and director credits that are ubiquitous in Arab music videos. Souleyman’s vocals have been sped up to match the fast tempo of the keyboard, but Souleyman himself is slow moving all the action takes place around him. Flashes of B-grade music videos depicting Souleyman, always sporting a keffiyeh and sunglasses, are spliced amongst the various celebrations. Waves of neon Arabic text are superimposed on scenes of men and women shimmying the dabke line dance. The song’s video - put together by Mark Gergis, the Iraqi-American producer behind Souleyman’s Western debut - is a chaotic compilation of Souleyman party clips. Though first heard in Syria in 1996, it was his breakthrough “hit” in the US. Some people call what he plays Syrian techno” - a kind of hype was born.ījörk’s YouTube plug was for Souleyman’s song “Leh Jani,” or “Why’d she come?” in Arabic.

That same year, Björk selected Souleyman for the NPR segment “You Must Hear This.” In her minimalist description - “The first time I heard Omar Souleyman was on YouTube. He’s from Syria.

I’ve been wondering what the future would hold for Souleyman since 2009, three years after his music was first introduced to American audiences with the album Highway to Hassake. This obscurity didn’t hinder his crossover into the US indie music scene - it was what made it possible. His backstory is one of performances at weddings, locally produced music videos, and trips to the Gulf for more shows and bigger paychecks. At the nightclubs in Damascus, where DJs mix Vanilla Ice with Cheb Khaled, Souleyman’s music isn’t on the playlist. THERE ARE HUGE POP STARS IN SYRIA, but Omar Souleyman isn’t one of them.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)